Agricultural Science and Plant Protection

Scientists in the Department of Agricultural Science and Plant Protection conduct research to discover safer and healthier ways to protect our food, health, resources, and homes from a variety of threats, including pests and disease.

To learn more please visit https://www.agscipp.msstate.edu/

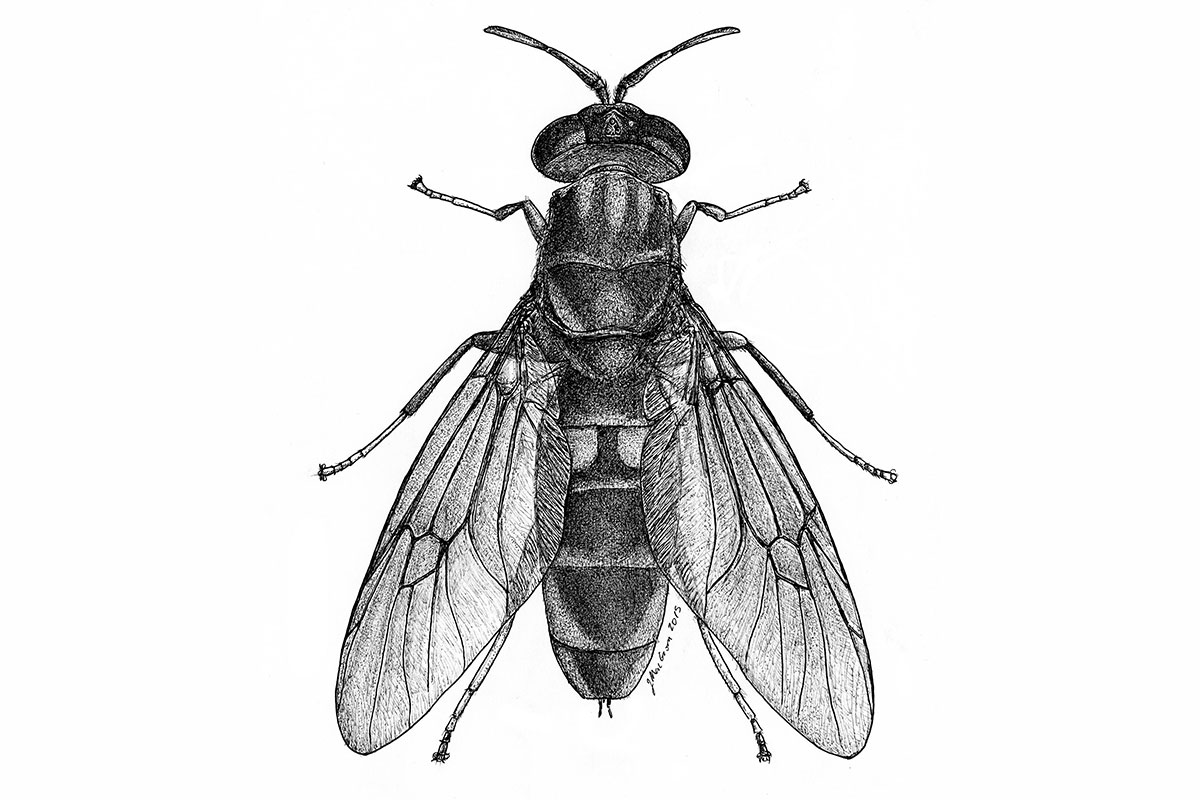

The black soldier fly, which turns agricultural waste into viable protein that can be used in feed for livestock such as chickens, may help fight food insecurity. John Schn...

Read More

While ambrosia beetles are believed to have been introduced into the U.S. from Asia in the early 2000s, they were not known to cause damage to healthy trees until the Read more

Butterflies are the oft-forgotten pollinators of Mississippi, but MAFES researchers are striving to change that. They have begun creating a massive inventory of the butterf...

Read more

MAFES scientists are leading efforts to detect and understand cotton leafroll dwarf virus (CLRDV), a newly emerging threat to U.S. cotton. Using advanced diagnostics and f...

Read More

Dr. JoVonn Hill, a MAFES scientist and assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology,

Entomology and Plant Pathology, has discovered a little ov...

Read More

Taproot decline is the seventh-leading cause of yield loss for soybean producers across Mississippi, and Xylaria, the novel fungal pathogen behind the disease, has...

Read more

One of the most consistent challenges producers face is yield loss from insects. Over the years, strides have been made to develop cultivars, specifically of cotton and cor...

Read more

In the midSouth, early-season pest management is a significant challenge to farmers. For insects, relatively mild winters combined with long, productive growing seasons cre...

Read More

Insect pressure in the field has long been a problem for row crop producers. Additionally, insects can damage stored grain, which can be a huge nuisance for farmers and gra...

Read More

Currently, the Magnolia State is experiencing its worst pine beetle outbreak in more than 30 years with more than 4,000 spots throughout the state's forests infested with t...

Read more

In the world of turf science, mysterious brown spots provide a peek at the multitude of bacteria and fungi that live within our lawns. Dr. Maria Tomaso-Peterson, a MAFES re...

Read More

Biomedical, physiological, and agricultural experts across Mississippi are joining together to protect one very important creature: the bee. Worker bees everywhere are bein...

Read more