The information presented on this page may be dated. It may refer to situations which have changed or people who are no longer affiliated with the university. It is archived as part of Mississippi State University's history.

Last year, Mississippi farms produced 730 million broilers, making poultry the biggest commodity for the state, totaling $2.88 billion in production value in a single year. Researchers in the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station are trying to answer foundational questions about the process of administering feed in order to help producers deliver feed in the most efficient and cost-effective manner possible.

Kelley Wamsley, MAFES researcher and assistant professor in the Department of Poultry Science, studies how the mechanics of the feed mill affect the physical and nutritional quality of feed, which ultimately affect bird performance and uniformity.

"Feed costs represent about 60 to 70 percent of the costs required to produce poultry; therefore the goal is to administer a nutritionally balanced feed as efficiently as possible," Wamsley said.

Her team selected samples from the beginning, middle, and end pans of several feed lines at different Mississippi farms. They separated out pellets and fines and established that phytase, an enzyme that makes it easier for birds to digest the phosphorus they need, segregated from the pellets and was found in the fines.

In commercial feed production, a nutritionist utilizes various available ingredients to formulate a least-cost diet specific to a bird's age, genetic strain, and production goal. These ingredients, which vary in physical properties (moisture, particle size, density, etc.), are then combined to make a uniform mixture.

The majority of broiler chickens (raised for meat) are fed pelleted diets. Pellets are formed by subjecting the mash feed to conditions of high heat, moisture, and pressure in a pellet mill. This additional process adds cost to feed, but provides benefits such as improved hygienic quality, decrease in the time and energy it takes for the bird to pick up the pellet, and less feed wasted.

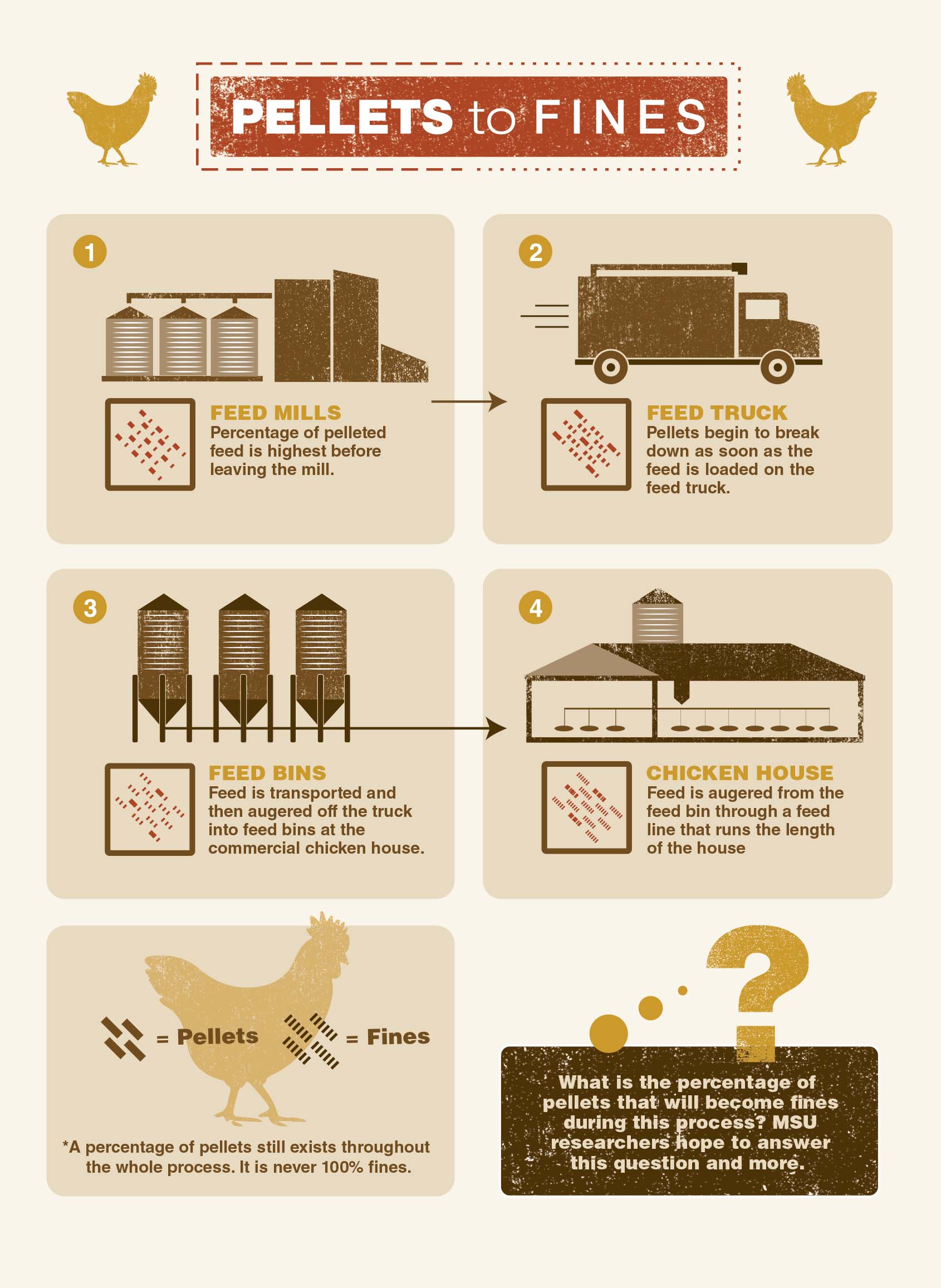

"Ideally, a nutritionally balanced diet is supplied in each pellet. However, pellet quality, in terms of physical form, is not always a priority at a commercial feed mill due to throughput constraints on the mill. Therefore, the outcome of pelleting feed is not 100 percent pellets, commercial feed is made up of a percentage of pellets and a percentage of fines. That percentage changes from the minute the feed leaves the mill until it reaches the last chicken at the end of the line," Wamsley explained. "Producing 100 percent pellets would be cost-prohibitive and would hinder production in a commercial setting. Not only would the feed itself be too expensive, the throughput in the mill occurs at such a pace that 100 percent pellets would slow the production of the feed to a crawl."

Wamsley sought to study phytase because it was a quantifiable ingredient occurring in a small amount that would ultimately affect bird performance and uniformity.

"Any ingredients added in small amounts, like phytase, will be of concern because once that ingredient breaks down, it's gone," she said. Wamsley continued, "A poor quality pellet breaks down a lot faster than a higher quality pellet, so a poor quality pellet will produce more fines than a higher quality pellet. Within those fines, one thing we are investigating is the effect of the segregation of nutrients. For instance, is the phytase showing up in the pellets or the fines? Answering questions like this helps us ultimately figure out what pellet quality means to integrators. We know feeding pelleted feed positively affects performance, but is a higher quality pellet worth the investment? Those are the big picture questions we'd like to help answer."

Several projects, led by Ben Sellers, one of Wamsley's former graduate students, evaluated how feed is altered as it is moved or augered throughout the feed system in a commercial broiler house. The goal was to assess how differing feed manufacture variables affect feed's physical form and nutrient composition/quality.

"We studied feed where the phytase was added to the mixer prior to when the pellets were formed, as well as phytase sprayed post-pelleting, on the finished pellets. We also compared feed that was 75 percent pellets/25 percent fines to feed that was 55 percent pellets/45 percent fines in this study," Sellers explained.

The team created the diet formulations and sent those formulas to West Virginia University, a partner on the project. WVU has a feed mill and can manufacture the feed. After that, the feed was sent to Mississippi State and augered into one of Mississippi State's commercial poultry houses. Researchers then examined how varying feed manufacturing techniques and feed form of the diets were affected by augering time and location within the house. Sellers assessed how well pellets stayed together at six points throughout the house. He also analyzed how much phytase stayed in the pellets and how much of the enzyme showed up in the fines.

"Dr. Wamsley's previous preliminary field research indicated phytase segregated rapidly. In this study, we were able to analyze how much of the phytase segregated based on location, time, and diet in a replicated manner," Sellers explained. "We determined that phytase showed up in the fines more readily, depending upon the timing of phytase application more than the quality per se."

Sellers, who graduated in December 2015 with a Master of Science in Poultry Science, won several awards for the research. He received two Certificates of Excellence for oral presentations at the 2014 Poultry Science Association annual meeting and the 2015 International Poultry Scientific Forum.

Chris McDaniel, professor in the Department of Poultry Science, assisted on the research. He emphasized how the project covered the entire production cycle.

"This project begins with the feed being created, formed into the pellets, modified, delivered into the house, fed to the birds, and the birds are processed and their performance and uniformity are measured."

McDaniel said the research led by Wamsley is ongoing and he is hopeful they will determine how the mechanics of feed delivery alter feed quality and feed form, ultimately impacting bird performance and uniformity.

"One day we would like to provide a benefit to cost value for proper pelleting of commercial feed. This information will help producers make better decisions in improving production and increasing their bottom line."