The effect of an infertile bull is easy to spot when he is the only bull in the pasture because the cows don't become pregnant. Unfortunately, by the time a cow-calf producer realizes a bull is infertile in this manner, it's usually too late to salvage the breeding season. In pastures with multiple bulls, an infertile or even subfertile bull, can be difficult to detect; but the resulting loss in productivity is still significant. Subfertility can have a big impact on a producer's bottom line, from fewer calves to delayed conception. Later-born calves are typically lighter at market, which directly reduces revenue. Despite these risks, many producers still skip a simple, inexpensive test called the breeding soundness evaluation, or BSE, which evaluates whether a bull can perform as expected. Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station (MAFES) researchers recently collaborated with researchers in the College of Veterinary Medicine to study the economic tradeoffs of adopting or skipping BSEs under different herd management strategies.

A breeding soundness evaluation, performed by a veterinarian and typically costing less than $100, assesses the physical and reproductive factors that determine whether a bull qualifies as a satisfactory potential breeder. Through a combination of structural and reproductive assessments, veterinarians evaluate overall soundness and reproductive anatomy, with testicular size serving as a key indicator of sperm-producing capacity. A semen sample is analyzed for motility and morphology. Bulls meeting established thresholds pass. While passing doesn't guarantee performance since the exam doesn't measure libido or pasture behavior, failing is a strong indication that the bull will not breed effectively.

The project originated from clinical experience. While practicing as a veterinarian in the field, Dr. Todd Gunderson often estimated the financial stakes of BSEs for clients, but when he returned to academia he sought a more rigorous assessment. During his population medicine residency in Mississippi State University's College of Veterinary Medicine, he teamed up with MAFES agricultural economists to build a model that quantifies those tradeoffs.

"As a veterinarian, you want to show the cost and payout of a service to your client. You make assumptions and sketch figures on the back of a napkin that may or may not be correct. When I got into my residency, I began thinking more critically about the value of BSEs," Gunderson said. "This project allowed us to examine my initial assumptions about BSEs more deeply and develop models that evaluate what makes the BSE a good investment for producers."

Dr. David Smith, professor and associate dean in the College of Veterinary Medicine who served as Gunderson's major professor during his residency, said the BSE reflects performance expectations.

"If you drive 10 miles per hour, tire condition may not matter too much," Smith said. "If you are racing in the Indy 500, tire quality becomes critical. You can get away with poor tires only when they are not under pressure. The BSE functions similarly."

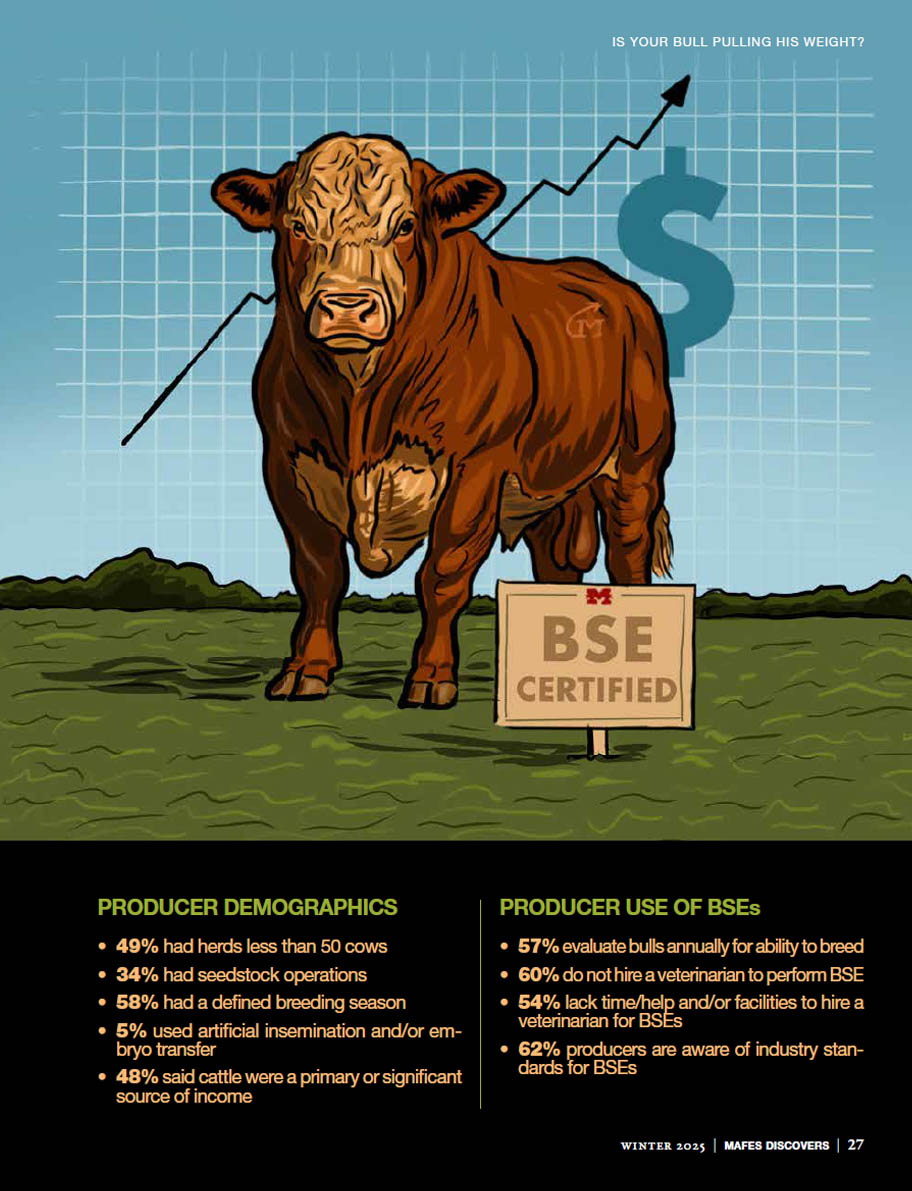

Before developing the model, the team surveyed Mississippi Cattlemen's Association members to better understand current BSE use across the state.

"We learned that producers who don't have a defined breeding season are much less likely to perform BSEs," Gunderson said. "If the bull stays out year-round, problems can be harder to detect."

To compare outcomes of BSE versus non-BSE strategies, the researchers used capital budgeting methods and Monte Carlo simulations. Capital budgeting evaluates long-term investments based on their potential to generate value over time while Monte Carlo simulations use repeated random sampling to model uncertainty and predict a range of possible outcomes for decision makers.

Dr. Kevin Kim, assistant professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and MSU Extension specialist, explained the team's approach.

"We used net present value (NPV), which accounts for the time value of money. This approach places greater weight on immediate costs and benefits, providing a more accurate picture of value over time," Kim said.

"Over a 50-year time horizon, NPV helped us calculate and compare long-term returns for herds that tested bulls versus those that didn't. Our results showed greater long-term value in herds that implemented BSE."

The team found that the value of the BSE depends on how the bull is managed. The BSE predicts whether a bull can breed approximately 25 cows within a 65- to 70-day breeding season. The researchers noted that defined breeding pressure matters. Without it, subfertility can go unnoticed. The shorter the breeding window, the greater the financial payoff of confirming bull fertility, since fewer cycles mean fewer opportunities to correct for subfertility.

"By not conducting BSEs, producers potentially incur opportunity costs that don't show up as a direct expense," Gunderson said. "These implicit losses still erode profitability."

Dr. Kalyn Coatney, professor in agricultural economics and MAFES scientist, said reproductive management style heavily influences the bottom line.

"If producers shift from year-around breeding to a controlled breeding season with fewer bulls per cow and a shorter timeframe, the pressure on the bull increases," Coatney said. "In that scenario, it makes financial sense for the producer to invest in BSE because he or she can't afford missed calves from a subfertile bull. In closely managed herds, BSE testing becomes a proactive investment."

The study also found that herds with higher cow-to-bull ratios, for example 33 cows to one bull, saw greater financial returns from BSE testing, as each bull's reproductive performance affected more calves. Even a modest five percent improvement in conception rates compounded over years produced measurable economic gains in the model. Although BSEs add a small veterinary expense and result in producers buying more bulls, the long-term model showed that gains in calf crop value far outweighed these costs under most management conditions.

The model demonstrated the scale of hidden losses associated with skipping testing.

"Subfertility represents a real economic loss," Gunderson said. "This model visualized that loss dynamically across years with risky outcomes."

A novel finding was that late conception proved especially costly.

"A cow bred in the second or third cycle one year is unlikely to breed early the next year," Gunderson said. "Late conception tends to persist, eventually leading to open cows. Maintaining an open cow still costs roughly $1,700 annually. When she produces no calf, that is a substantial loss."

Whether the problem originates from the bull or management factors, the result is the same: open cows and unrealized revenue.

The research demonstrated that reproductive efficiency is both a biological concern and an important business decision. Through thoughtful herd management and the strategic use of BSE testing, producers can reduce production inefficiencies, limit financial risk, and improve calf crop performance and returns. Because profitability varied with management intensity, the researchers emphasized that BSE adoption should be evaluated case by case.

The CVM/MAFES study equips producers with clearer financial insight so they can make sound decisions that support herd health and economic resilience.

This research is funded by the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station.

If you drive 10 miles per hour, tire condition may not matter too much. If you are racing in the Indy 500, tire quality becomes critical. You can get away with poor tires only when they are not under pressure. The BSE functions similarly.

Dr. David Smith

Behind the Science

Kalyn Coatney

Professor

Education: B.S., Agricultural Business; M.S., Agricultural Economics; Ph.D., Economics, University of Wyoming

Years At MSU: 15

Focus: Applied game theory and industrial organization

Passion At Work: Conducting innovative research to solve real-world economic problems that ultimately has a measurable positive impact on agriculture and food systems.

Kevin Kim

Assistant Professor

Education: B.B.A., Finance, University of Notre Dame; M.A., Business Administration; Ph.D., Agricultural Economics, The Ohio State University

Years At MSU: 4

Focus: Agricultural finance

Passion At Work: I am passionate about advancing agricultural finance and translating that knowledge into practical, accessible guidance for producers through Extension.

Todd Gunderson

Clinical Assistant Professor of Beef Production Medicine, Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine

Education: B.S., Chemical Engineering, Brigham Young University; D.V.M., Washington State University; M.S. Veterinary Biomedical Science, Mississippi State University

Years At MSU: 2021-2024

Focus: Epidemiology and production animal medicine

Passion At Work: Addressing complex problems in veterinary medicine with applied research and thoughtful pedagogy.

David Smith

Associate Dean for Research and Graduate Studies, Professor

Education: B.S., Agriculture; D.V.M., Veterinary Medicine; Ph.D., Veterinary Preventive Medicine, The Ohio State University

Years At MSU: 13

Focus: My research applies veterinary epidemiology to improve the health of animals and people.

Passion At Work: I believe my most important task is to help students achieve their career aspirations.