The information presented on this page may be dated. It may refer to situations which have changed or people who are no longer affiliated with the university. It is archived as part of Mississippi State University's history.

Foodborne illnesses are a serious concern among producers, processors and consumers alike. Each year some 2 million individuals in the U.S. contract foodborne illnesses from Salmonella and Campylobacter.

Perhaps the reason these two bacteria are prevalent sources of foodborne illness is their existence in healthy poultry and beef.

Consumers are the last line of defense yet the most effective in preventing foodborne illness by fully cooking food and following other safe food handling practices.

"The easiest way to prevent illness from poultry is to make sure it is fully cooked to an internal temperature of 165 degrees Fahrenheit," said Chander Sharma, Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station researcher and assistant professor in the Department of Poultry Science. "By cooking food completely, consumers will rid all poultry products of any foodborne bacteria."

Other precautions include preventing cross-contamination by keeping utensils and surface areas clean, practicing good hygiene by frequently washing hands during meal preparation, storing food at proper temperatures to keep hot food hot and cold food cold, and choosing a safe source for food.

While consumers should practice safe food handling to prevent contracting bacteria that can cause an uncomfortable and unnecessary illness, scientists at Mississippi State are working to rid poultry of these common bacteria before they ever leave the processing plant.

Scientists recently tested the use of lauric arginate, an antimicrobial compound approved by the USDA, as a processing aid to assist in the fight against Campylobacter jejuni and Salmonella. Scientists are also researching if the compound extends the shelf life of poultry, which is currently limited to a week.

"Lauric arginate has been tested against various foodborne pathogens including Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella and E. coli," Sharma said. "However, there is limited data on the use of lauric arginate against Campylobacter in the meat system."

Foodborne illness from Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) affects nearly one million people each year. To determine the effectiveness of lauric arginate against C. jejuni and Salmonella scientists conducted a series of experiments.

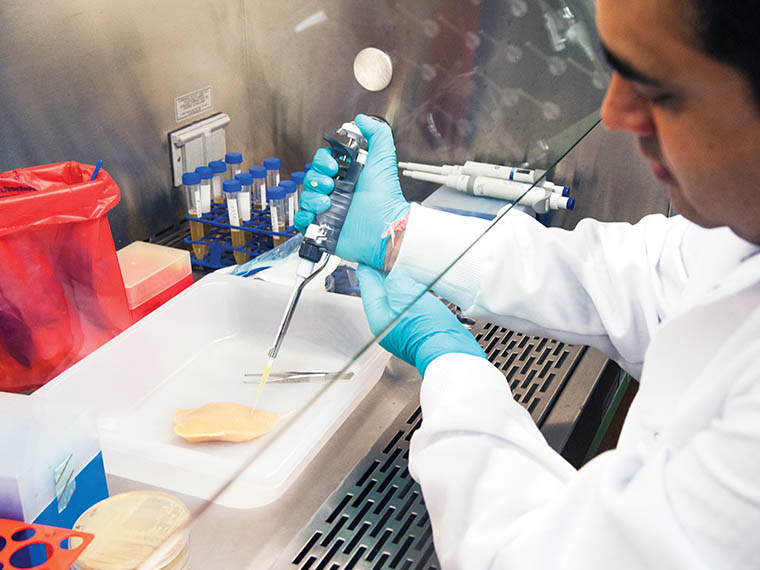

The first experiment tested the effectiveness of the preservative on a pure culture of C. jejuni. Samples of the bacteria were placed in a test tube along with varying solutions of the preservative. Lauric arginate was very effective at destroying the bacteria with no detectable survivors.

Scientists then coated the outside of raw chicken breast fillets with C. jejuni, treated it with lauric arginate, packaged and refrigerated the meat for a week.

Samples were taken periodically to determine if lauric arginate was effective in removing the bacteria.

"At day seven, we had a 94 to 95 percent reduction of Campylobacter jejuni in the inoculated chicken breast," Sharma said. "The preservative reduced Salmonella by 80 to 90 percent."

Findings show that lauric arginate is very effective at controlling Campylobacter jejuni in raw poultry products. It is also good at controlling Salmonella, Sharma added.

The findings could be used by poultry processors who use a variety of USDA-approved antimicrobials during chilling and post chilling.

"Poultry processors chill birds immediately after slaughter to prevent bacterial growth either through air chilling or water chilling," Sharma said. "Lauric arginate may be applied during post chill to control foodborne bacteria."

In a separate experiment, scientists treated raw chicken breast fillets with lauric arginate to determine if the preservative extends the shelf life of poultry.

"The shelf life of poultry is typically seven days, and when you consider the transportation of poultry: from processing to retail grocery store to your home, poultry has a very short shelf life," Sharma said. "If we can safely extend this time, everyone benefits."

To determine if the shelf life is extended, scientists measure mesophilic bacteria-those responsible for decomposition-and psychrotrophic bacteria-those responsible for spoilage of refrigerated food.

The preservative had little effect on these bacteria, suggesting that further work may need to be done with higher rates of application considered.

With consumer demand for poultry and non-preservative-based foods increasing, scientists are also studying the use of bacteriophage in poultry processing. Bacteriophage is a virus that attacks bacteria. It is very specific in targeting its host.

"In our trials, we found bacteriophage reduces Salmonella by 90 percent in chicken and turkey meat when applied during the post chill processing," Sharma said. "More research is needed but bacteriophage may be the answer to a non-preservative-based additive to assist in the fight against foodborne illnesses."

When applied sequentially with other USDA-approved antimicrobials, bacteriophage reduced Salmonella by 99 percent, Sharma added.

"The use of bacteriophage is promising as it could become an additive to the processing, not a chemical," Sharma said. "More research is needed. We need to determine if Salmonella or other foodborne bacteria can develop immunity to bacteriophage."

Behind the Science

Chander Sharma

Assistant Professor

Education: DVM, M.S., Veterinary Public Health; Punjab Agricultural University (India); Ph.D., Food Science, University of Florida

Years At MSU: 4

Focus: Microbial food safety in poultry

Passion At Work: My favorite thing is getting undergraduate and graduate students involved in food safety research and teaching students the principles and value of food safety.