The information presented on this page may be dated. It may refer to situations which have changed or people who are no longer affiliated with the university. It is archived as part of Mississippi State University's history.

It's genetic. A phrase often stated to explain physical and behavioral characteristics as well as health issues. Breast cancer, heart disease, and diabetes are just a few of the health issues thought to have an inheritable component.

For Samantha Sockwell, a food science, nutrition and health promotion undergraduate student, the idea of inheriting a health disorder was unsettling. When a member of her family became ill and the likely cause was linked to genetics, she decided to make a change in her family's history and turned to nutrition.

"I have always been interested in nutrition and exercise but didn't really understand the science behind eating healthy," Sockwell said. "When I realized I could have a career as a registered dietitian, it seemed to be a good fit and could provide the knowledge I needed to break the cycle of inherited health disorders."

She has turned her interest in nutrition and genetics into knowledge as she works as an undergraduate research scholar. In her research, she is looking at the role of taste genes as a predisposition for food choices.

Recruiting among her peers, Sockwell and others who proceeded her in the research have recruited about 750 students to participate. Their goal is to reach 1,000 individuals.

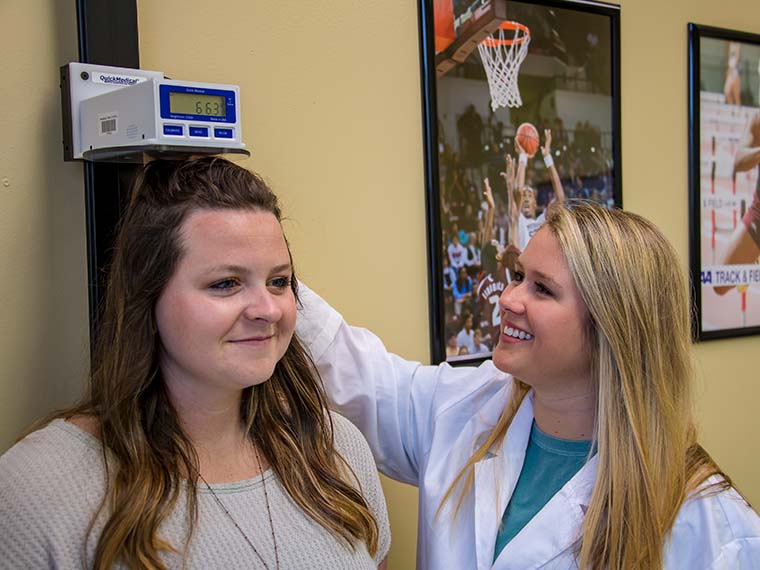

Those recruited complete a lengthy National Institutes of Health diet history questionnaire. Upon completion of the survey, a saliva sample is taken and body composition is measured with Tanita, a body composition analyzer that measures body fat percentage, hydration level, lean body weight, and more.

The data from the questionnaire and the body composition measurements are entered into a statistics software program while saliva is used for DNA extraction and evaluation of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the taste receptor genes.

"There are thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms in taste receptor genes and we are comparing different ones to different eating patterns to determine if there is a genetic predisposition to diet preferences," she said. "If diet preferences have genetic background, we can begin to educate people on how to make changes to their diet to overcome these predispositions."

The ongoing research is in its third year. Working under the direction of Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station scientist, Dr. Terezie Mosby, undergraduate students have already found numerous outcomes from the study.

Based on the analysis of the questionnaire, Sockwell was able to study the association between sugar consumption, caffeine consumption, and body fat among female college students. This study found that as caffeine intake increases, sucrose intake also increases, regardless of weight.

"It is important to understand the dietary habits of young adults to help tailor obesity invention programs in this population," Sockwell said. "Excessive sugar and caffeine intake, both through sweetened coffee beverages and energy drinks, are consumed in significant amounts by young people and can be detrimental."

In a separate study, Sockwell assisted Nicole Reeder, a graduate student in food science, nutrition and health promotion, to determine the relationships between dietary fat composition and obesity in young females.

The study, which was also based on analysis of the NIH diet history questionnaire, found that females with body fat over 30 percent consumed more cholesterol and trans fat compared to those with lower body fat. The difference in the type of fat consumed was partially explained by the amount of red meat consumed, which is higher in fat content compared to other sources of protein.

Sockwell's research on genetic predispositions for diet preferences will continue through the end of 2018. Her ultimate goal is to educate individuals on how to break the familial genetic health disorder cycle.

"If you know your genetic predispositions, then you can modify your lifestyle including diet to overcome those predispositions," Sockwell said. "Our goal is to educate individuals so that they can live happy, healthy lives and break the pattern of increased inherited risk for chronic disease development."